“Write what you know” is one of the most common, and perhaps most debated, bits of advice given to aspiring fiction writers.

While making my first attempts at stories and novels, I interpreted this advice in the most literal way: I thought it meant that I was supposed to comb through events in my fairly unremarkable life, pull out the ones that had the most narrative potential, and somehow transform them into compelling works of fiction.

My rather smug response to this tactic was No thanks. After all, I wanted to write about con artists and lapsed faith healers, about costume-party horrors inspired by those in “The Masque of the Red Death.” What possible relevance could my life experiences have to these characters and scenarios?

But as the years passed–as I drafted, revised, and now and then discarded various stories and novels–I came to see this advice in a different, more generous light, much as writer Keith Cronin has done. In an article explaining his own rethinking of “Write what you know,” Cronin shares an observation he heard at a conference, from writer Barbara O’Neal: “We’re all stuck with our own stories.”

In explaining O’Neal’s remark, Cronin writes:

Barbara wasn’t telling us that we needed to base the plots of our novels and stories on our actual personal lives. Instead, she was suggesting that if we focused our writing on exploring the ideas and feelings that meant the most to us, the result would be that our stories would be imbued with a correspondingly deep level of emotional intensity and personal conviction.”

I couldn’t agree with Cronin (and O’Neal) more, and I can only hope that in my fiction, I’ve done justice to the ideas and feelings that have struck the deepest chords in me–for example, the powers of self-expression and quiet rebellion, which I explore in my novel Marion Hatley, and the long reach of guilt, regret, and loss, which is central to my novel In This Ground.

Furthermore, it’s not possible for me to write with authenticity about characters’ desires and struggles without drawing on my own experiences of desiring and struggling, and of generally making my way in the world. Depending on circumstance, I might draw on particular memories or on a subconscious-level sense of what feels real and true for a given situation, even if it’s one I’ve never found myself in. That sense comes, necessarily, from my own experiences.

I should also acknowledge that personal experiences and family stories have provided valuable points of departure for my novels and stories, even if these works aren’t based directly on those experiences and stories. For example, as I discuss in another blog post, my mother’s descriptions of the uncomfortable corsets my Grandma Cleo used to wear inspired the crowning achievement of the central character in my novel Marion Hatley. A Depression-era seamstress, Marion invents a corset that is as comfortable as it is beautiful, bringing the daily, private trials of corset-wearing women–especially working women–to an end.

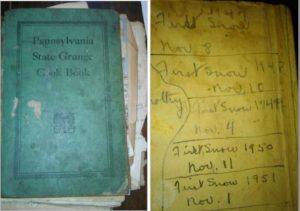

My Grandma Cleo’s battered 1925 edition of the Pennsylvania State Grange Cook Book offered another source of inspiration for my fiction. The recipes in the cookbook are so strange-sounding they border on exotic—for corn oysters, vegetable shortcake, and Punch for Sixty Grangers, to name just a few. But my main interest has always been in the cookbook’s inside front and back covers, which my grandmother used to record the first snows of many years, and various other seemingly ordinary details. None of these strike me as overly personal, but they offer an intriguing glimpse into the life of a woman I was just getting to know when she died.

I never got the opportunity to ask my grandmother how she decided what facts or observations were important enough to write down, in a cookbook of all places. My desire to explore this mystery, ultimately an unsolvable one, inspired a short story that was published in the Mulberry Fork Review. Although, like me, the central character has inherited a cookbook/diary, her story is quite different from my own. But, like me, she can’t help but try to fit together the scattered puzzle pieces that the dead so often leave behind. Without drawing on my own desires to make sense of such things, I couldn’t have written about hers in a way that would feel real and true.