I’ve never been big on buying things. I shop for groceries, of course, and replace clothes, shoes, and other necessities whenever the current models start looking trashy or worn. In other words, for me, shopping tends to be something to be gotten through, nothing inherently rewarding or fun.

Except for when it comes to books. For a long time, I’ve been a shameless acquirer of print books (I haven’t caught the e-book bug and doubt I ever will), and I give myself pretty free rein on spending. As one example, if I can’t make myself wait for the paperback edition of some new book I’m eager to read, I won’t hesitate to splurge on the hardcover edition. No doubt, I could economize by going to the library. But I prefer to buy books, mainly to support writers and bookstores, secondarily because I’m comforted by their presence. A home without shelves and stacks of books–well, it wouldn’t really feel like home.

Yet there’s only so much room for all these books. So from time to time, I distribute those that I’ve finished (and am sure I won’t reread) among the little libraries that have popped up throughout the neighborhood, hoping they’ll catch the interest of passers-by.

But there are certain books I’ll never give away–not so much because I know I’ll reread them, though I might, but because they’re strongly associated with people I’ve loved, or with my evolution as a reader and writer.

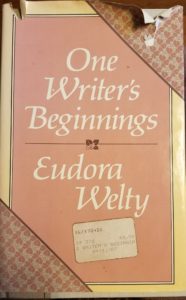

One of these books is One Writer’s Beginnings, a brief autobiography by Eudora Welty, whose fiction mesmerized me as an undergraduate and helped inspire me to become a writer. Her novels and stories showed me the deep dives into character, setting, and conflict that the finest writing can achieve. They also revealed the power of the strange and mythological in stories, elements that I can’t remember incorporating into my fiction pre-Welty, at least in part because I lacked the confidence that her work helped build in me.

One Writer’s Beginnings inspired me because, collectively, the memories that Welty shares in it suggest that the desire to read, hear, and tell stories comes to us early and naturally, and persists over time. For me, this made writing fiction seem like a less extraordinary, and therefore less daunting, endeavor. And it made me feel like less of a weirdo for wanting to spend so much time on it.

Also, because Welty’s insights about becoming a storyteller are so personal, so tied to memories of her parents’ encouragement of her as a young reader and writer, I felt–dare I say?–love radiating from every page of the book. Consigning it to a little-library shelf would be like tossing letters I’d received from a beloved family member–heart-felt, life-changing letters–into the trash.

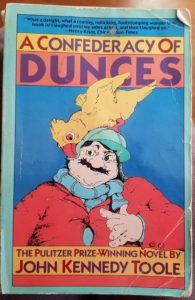

Another book I won’t let go of is my well-worn copy of A Confederacy of Dunces, by John Kennedy Toole. Years ago, while reading it during a visit with my parents in Ohio, I laughed so hard at certain sections that my dad (one of the funniest people I’ve known) got curious. Curious enough that I started to read some choice passages to him, and got him laughing, too. After my visit, he read the book for himself and enjoyed it as much as I did. Our mutual admiration of the novel, and our later conversations about it, helped make it a relic of the special connection we had–a relic that’s become even more precious to me now that my father is gone.

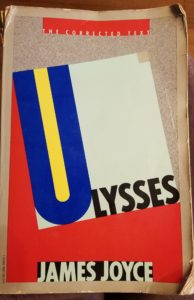

A relic of my connection to my late mother is Ulysses, of all books. During my senior year of college, she treated us to a circuit of England and Scotland, by train, and for some reason, I thought this was just the time to wade into the challenging, and weighty, 650-pager. I can’t remember how much of the novel I read during the trip–20 or 30 pages would be a generous estimate. What I do remember is hauling it, and a good amount of luggage, from train to inn to train. As we schlepped and rolled from town to town, my mom and I started joking about what a fine tour Ulysses (not the highly regarded work of literature, but the four-pound block of paper) was getting, and what a good workout I was getting. Years later, that joking resurfaced whenever the trip came up in our conversations. (When I finally got through Ulysses, about ten years after our journey, my mother was among the first to know.)

Although I could mention many other books I feel the need to hold on to, I’ll single out just one more: my Grandma Cleo’s battered 1925 edition of the Pennsylvania State Grange Cook Book, with recipes so strange-sounding they border on exotic—for corn oysters, vegetable shortcake, and Punch for Sixty Grangers, to name just a few. But my main interest has always been in the cookbook’s inside front and back covers, which my grandmother used to record the first snows of many years, and various other seemingly ordinary details. None of these strike me as overly personal, but they offer an intriguing glimpse into the life of a woman I was just getting to know when she died. And the notes she kept ended up inspiring a short story, as I discuss in another blog post.

As long as I’m still cooking, literally and figuratively, Grandma’s book will occupy my cookbook shelf, within easy reach of the stove.

I love this trip through your treasured books. You have such a friendly warm voice. Thanks!

Thanks so much, Karen!

Beth, so great that you were able to distill such a finite list–one so intensely personal, but displaying so wide a range of loving interests (love and interests?).

Thanks so much for your kind words, Steve!

Really enjoyed this blog article. Much thanks again. Awesome. Felicity Hillie Ahrens