One of the most common questions I’m asked during readings and interviews is, “Do you create an outline before writing your novels?”

The answer is a resounding “Yes.” I find rough outlines invaluable for working out story arcs for first drafts, and for helping me complete those drafts in a reasonable time frame. In the absence of such advance planning, I once spent 12 years writing and revising a novel, which I vow to never do again.

But I never hew strictly to outlines. They’re just general guides, and once I get down to writing, stories and characters inevitably take on a life of their own, the kind of thing I live for as a writer. These moments can feel transcendent, and they are one of the main reasons I write.

Outlines aren’t the only tools I use to complete relatively coherent first drafts, ones that have some narrative momentum and (I hope) fully realized characters. Next, I’ll describe some of these tools and how they’ve helped me figure out, and navigate my way through, novel-length stories.

Storyboards: Avoiding “Saggy Middles”

You might have heard of storyboards from descriptions of the entertainment business. One example of them is the comic-strip-like graphics that directors or cinematographers create to show crew members how scenes in a movie or TV show should play out visually.

In fiction writing, storyboards tend to be more prosaic. Remember those diagrams of story plots from middle-school English class, the ones showing rising action, the climax, and falling action? That’s pretty much what I mean, though fiction storyboards are usually a bit more detailed.

To my mind, the main benefit of a storyboard is that it can help ensure that a novel has momentum. Have you ever gotten pulled right into a novel (or movie or TV show), finding the plot and characters immediately compelling, only to sense–typically, somewhere in the middle of the story–that the narrative is starting to go adrift or get bogged down? Storyboarding is a good way to steer clear of this problem, helping the writer keep the plot moving and make sure there’s something at stake for the protagonist in every chapter and scene.

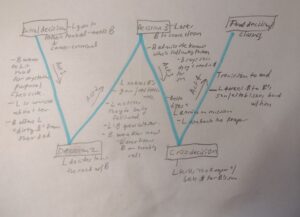

The storyboard I sketched out for my novel I Mean You No Harm follows a W structure, a fairly popular storyboarding technique.

The W storyboard is based on a common structure for screenplays, with each line of the “W” representing one of four acts. Early in the process of writing the novel, I realized that the story would be driven largely by a series of decisions the protagonist would have to make–a major one being a decision to go on a mysterious, and ultimately quite dangerous, road trip with her half-sister. So I used the “W” to plot out the key decisions driving the protagonist, and each act of the novel. I also jotted down the consequences of each decision and how they would further drive the action.

I should say that I don’t create storyboards for every novel. Because I Mean You No Harm was my first work of suspense, a genre in which readers expect things to move along at a fairly brisk clip, I decided that this strategy would be especially helpful at the early stages of writing the book. After sketching out the main plot points on the W diagram, I fleshed them out in a Word doc, approximating the sort of brainstorming and outlining I do for other novels.

Information Dumps: Finding Stories through Characters

The novel I’m working on now had perhaps the longest gestation phase of any book I’ve written. I knew that I wanted to write about a farmer who is trying to hold onto her land even though everything seems to be conspiring against her. And I wanted her to live in the shadow of a legend surrounding her great-great grandmother, who was rumored to have killed to keep the farm. But I wasn’t sure how to tell a story that connected these elements in an interesting way.

Before I could get a handle on an overall arc for the story, all these characters started coming to mind: not just the protagonist but also a developer who’s pressuring her to sell her land, a cousin who’s in league with the developer, and various loved ones of the protagonist who have died and, therefore, can support her only in spirit as she struggles to hold onto her farm (her husband, parents, and only sibling, who’d been regarded as far more capable than the protagonist of managing the farm).

Then there was the great-grandmother. How, I wondered, could I make her and her own fight to keep the farm relevant in the present?

Because the characters seemed to be taking precedence over any sensible plot, I decided to let them have the floor. Specifically, for each character, I jotted down every thought that came to mind about them: their history, desires, motivations, and so on. In time, connections between characters started to emerge, as did ideas for an overall story arc. (Often, these ideas came to me when I was away from my computer, usually when I was out for a run.) In the process, I figured out a way to integrate the great-grandmother into the present action of the story. I also figured out a possible structure for the novel, one that aims to make the farm’s (and the protagonist’s) past as vivid as its present.

I did so much idea dumping that, eventually, I began to wonder if it had evolved into a form of procrastination. At some point, I took a leap of faith and began writing the first chapters of the novel, and now I’m about a third of the way through the first draft. Although a large proportion of the ideas from my info-dump files will never make it into the novel, for now at least those ideas are informing nearly every scene, and almost every thought and action of the characters.

Lay-of-the-Land Visuals: Keeping Details Straight and Consistent

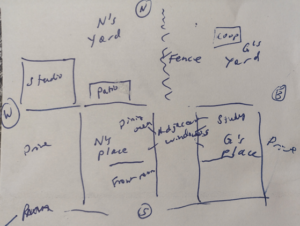

When I write, the actions in my novels play out in my mind like scenes from a film, and I exist within the physical spaces of the scenes. In the case of my forthcoming novel, The Inhabitants, the main physical spaces are two adjacent houses–one occupied by the protagonist, Nilda, and the other by a chemist who ends up playing a troubling role in Nilda’s life. But there are also scenes in Nilda’s on-property art studio and in the back yards of her place and her neighbor’s.

While working on The Inhabitants and other novels, I’ve sometimes had an unclear handle on–or forgotten, from scene to scene–the relationship between one space and another. For example, while writing The Inhabitants, I wondered how Nilda might be able to spy on goings-on at the chemist’s from a downstairs window. I also wondered how much of his space would come into view. Also, I sometimes got tripped up over the geographical orientation of things. How, for instance, could Nora view the sunset from her studio if it had a northern exposure?

To answer these questions, and to ensure consistency of spatial information from scene to scene, I came up with a crude drawing of Nilda’s and the chemist’s properties and referred to it whenever I needed reminders about spatial orientation.

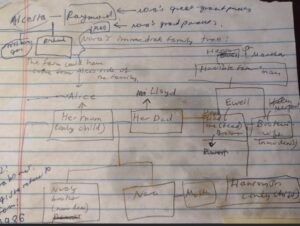

The farm novel presents another potential source of confusion: the cross-generational nature of the story. It can be surprisingly easy, for example, to forget who was married to whom, who parented whom, and so on. So I sketched out a very rough family tree to help me keep track of everything.

I also created a list of birth and death dates to make sure that I have a handle on characters’ ages in the present and in the past and that I don’t introduce any consistencies.

Over time, I’ve come to believe that if some aspect of writing a novel confounds me, especially in the early stages, I’ll find a way to figure things out. I’m glad I’ve identified a few tools to help me forge ahead.

Hi Beth,

Love this window on to your process, especially the idea dumping of every character’s thought, desire, motivation. Brilliant. I can’t wait to read this book AND The Inhabitants!

Thanks so much, Margaret! I can’t wait to read your book as well!

Hi Beth, this view of your creative process is generous of you and valuable for us. Thanks and best wishes for continued success!

Larry

Thanks so much for your kind words, Larry!

Nothing writes itself, but how I wish it did! Interesting post, Beth!

Jackie

Thanks so much for your kind words, Jackie!