Almost fifteen years ago, I suffered a traumatic brain injury–not from a car accident or some other dramatic event. For reasons that never became clear, I fainted for the first time in my life, fracturing my skull on the floor of a supermarket.

The path to recovery was long and uncertain. One consequence was that I wasn’t sure that I’d be able to write again. But with time, I was able to return to writing and to my old life in general, the only lasting effect–as far as I can perceive–being a diminished sense of smell.

Several times since the injury (especially as its ten-year anniversary approached), I told myself I should write about the experience. But eventually, I’d come around to thinking, “What is there to say, really?” Although I was deeply grateful to have recovered from a life-threatening injury, my TBI wasn’t remarkable on a grand scale, nor was my recovery; every year, millions of people suffer TBIs, and to varying degrees, many of them recover.

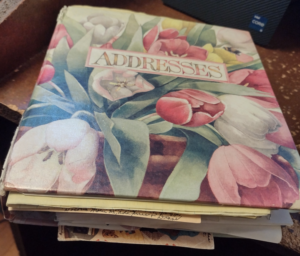

Then, something changed my mind: something I discovered in my late mother’s address book. Of all the possessions of hers that I’ve held onto, it may be the one that I value the most, because it served as an impromptu journal for her, a record of her ongoing interest in the lives of friends and family, which she maintained until she couldn’t. In the address book’s margins or in sticky notes, she wrote brief updates about various loved ones listed in the pages.

About a year and a half ago, while searching the book for a relative’s address, I came across a sheet of notepaper my mother must have brought on one of her visits to me in the hospital. On it, she recorded the details of my TBI: Traumatic brain injury with bilateral parietal subarachnoid hemorrhages, contusions of the left anterior and posterior temporal lobes and left frontal lobe; also … an occipital fracture

I was moved by the care that she took with these notes, and by the fact that she’d made them at all. I was also struck, once again, by the precision and beauty of her cursive, a feature of the many cards and letters she’d sent me over the years, until dementia made her unable to write. On my hunt for my relative’s address, I rediscovered what must have been some of her final entries, her cursive–by that time crabbed and wavering–giving evidence of her decline.

This evidence reminded me of a fear that took root in me in the wake of my TBI: that I, too, would develop dementia. TBI made me far more susceptible to the condition than I’d been before the injury, and the fact that a close relative developed dementia only amplified that risk. Revisiting my mother’s address book prompted me to also revisit memories of her cognitive decline and of my struggle to regain my abilities to read, write, and generally function in the world. I began to write about the connections between these memories, my experiences becoming a sort of window on my mother’s and vice versa.

Eventually, these reflections evolved into an essay titled “My Injured Brain,” and I submitted the essay to Ars Medica, a journal that publishes creative nonfiction, fiction, poetry, and visual art related to “the body, health, wellness, and encounters within the medical system.” I’m pleased that Ars Medica accepted the essay, which you can read here if you’d like. And I’m grateful for all the ways in which my mom inspired me.